JavaScript Modules Explained

Rafa Romero Dios

28 Jul 2022

•

7 min read

JavaScript modules is a topic that has become more and more popular in the last few years for two main reasons. First - because of the growth of NodeJS' popularity and its ecosystem, and second, as it became a standard since ECMAScript 2015 version, i.e. ES6 (the 6th Edition of the ECMA-262 standard). This standard and official versions of modules feature is known as ESM (ECMAScript Modules)

However, this approach to organise our code and share it between different files (so to speak), has existed for many years, because of the lack of commonly accepted forms of JavaScript module units which could be reusable in environments different from that provided by conventional web browsers running JS scripts.

Even before the existing implementations or solutions focused on Module Architecture, other solutions were created in order to create with just pure vanilla JS (and no use of any Module implementation) a module: we are talking about IIFE.

In this article we will be focusing on ESM, because as we said before, this is the official standard and the way to go. But before we dive deeper into the topic, it is important to have a picture of the panorama before the arrival of ESM and how we got here.

Let’s note (one more time) the importance of a feature that’s been requested and previously implemented by the community, and that is no longer a standard. The contribution of the community is crucial for the growth and evolution of the language, in our case, of JavaScript.

A bit of history: AMD, CJS and more

So, without an official way or API to create modules, the developers community (as always) needed to implement something to achieve these goals. For many years, two players have dominated over the rest. The AMD (Asynchronous Module Definition) on one side, implemented mainly by RequireJS, and the CJS (CommonJS) on the other, used mainly by NodeJS. Later, other players took action, in order to bring some peace: UMD (Universal Module Definition) and SystemJS. Both tried to create a way to make AMD compatible with SystemJS.

Now let’s see a brief definition of each one.

IIFE

IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression) was the first way to define a module without using anything else. Based on the Revealing Module Pattern, IIFEs simulate a context where we have private data (the one defined in the function) and public data (the one exposed via the function's return)

var myPersonalInfoModule = function () {

// those variables are private and are not accessible from outside

let name = "Mary";

let surname = "Mcfly";

// those methods are private and are not accessible from outside

function concatenateName() {

return `${name} ${surname}`

}

function printName(){

console.log(concatenateName())

}

function setName( newName ) {

name = newName;

}

function setSurname( newSurname ) {

surname = newSurname;

}

// this way we expose those variables and methods we want

return {

setName: setName,

setSurname: setSurname,

printFullName: printName

};

}();

// example of use

myPersonalInfoModule.setName( "Doc" );

myPersonalInfoModule.setSurname( "Brown" );

CJS (CommonJS)

Commons JS was the first architecture that became popular. The module architecture that was defined was mainly focused on non-browser environments. It was thought over a synchronous architecture. The most known implementation is the one that uses NodeJS.

Below is a snippet of code on how to define and use modules:

// exporting or defining

module.exports = function myUtilsModule(n) {

// your module's code

}

// importing

const myUtilsModule = require('path/to/myUtilsModule.js');

// now you can use the feature exposed by myUtilsModule.

AMD (Asynchronous Module Definition)

As we can read in the official repo, the Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD) API specifies a mechanism for defining modules such that the module and its dependencies can be asynchronously loaded. This is particularly well suited for the browser environment where synchronous loading of modules incurs performance, usability, debugging, and cross-domain access problems. So, to sum up, AMD appeared with the goal of solving those things that in some way were not properly implemented or covered by CJS. The most known implementation of AMD is RequireJS

Find below a snippet of code on how to define modules and use them:

// exporting or defining. The file is called myUtilsModule.js

define(function (dep1, dep2) {

// your module's code

return function () {};

});

// importing

requirejs(["myUtilsModule"], function(myUtilsModule) {

// now you can use the feature exposed by myUtilsModule.

});

UMD (Universal Module Definition)

UMD, as described in the official repo, attempts to offer compatibility with the most popular script loaders. In many cases it uses AMD as a base, with special-casing added to handle CommonJS compatibility. UMD, as its name indicates, works both in front and back end environments.

The pattern has two parts: an IIFE where it is checked the module loader implemented by the user, and an anonymous function that creates the module:

(function(root, factory) {

if (typeof define === 'function' && define.amd) {

// AMD. Register as an anonymous module.

define(['exports', 'b'], factory);

} else if (typeof exports === 'object' && typeof exports.nodeName !== 'string') {

// CommonJS

factory(exports, require('b'));

} else {

// Browser globals

factory((root.commonJsStrict = {}), root.b);

}

}(this, function(exports, b) {

//use b in some fashion.

// attach properties to the exports object to define

// the exported module properties.

exports.action = function() {};

}));

SJS (SystemJS)

SJS, as described in the official repo, is a hookable, standards-based module loader. It provides a workflow where code is written for production workflows of native ES modules in browsers. It can load modules synchronously or asynchronously

Supports top-level await, dynamic import, circular references and live bindings, import.meta.url, module types, import maps, integrity and Content Security Policy with compatibility in older browsers back to IE11.

For the case of SJS, we will see an example where a module exportable ready by defined in another file is imported from a JS code executing in a web environment:

main.js file

// exporting or defining

var myUtilsModule = function (n) {

var myMethod = function(){

// your module's code

}

return {

myMethod: myMethod

}

}()

Now, from our index.html:

// exporting or defining

<html>

<head>

<script src="path/to/systemjs"></script>

<head>

<body>

<script>

System.import('path/to/main.js').then(function(){

myMethod();

})

</script>

</body>

</html>

ESM

ESM, ES6 Modules or EcmaScript Modules, are the standard definition for JavaScript modules. As its name says, they were born in 2015 with the sixth version of ES with the aim to standardise all the module's ecosystem and offer a native way of creating JS modules. A good summary to describe ES Modules is the following one:

ES Modules takes the best of previous definitions with a simplified API

Let's describe the highlights of ES Modules:

- Support for synchronous and asynchronous module loading

- Compatible with both frontend and backend environments

- Support for Bare import by using import maps

- Possible to load directly from URL or CDN

- Compatible with three-shaking by default

Before going deeper into the technical specification, let's see a basic example just to set a basis where to start from

// myModule.js

export const endpoint = 'api.com/endpoint';

// main.js

import { endpoint } from "./myModule.js";

Exporting

We can export or expose different types of data: from variables to functions, objects and whole classes. From now on, we will call them entities.

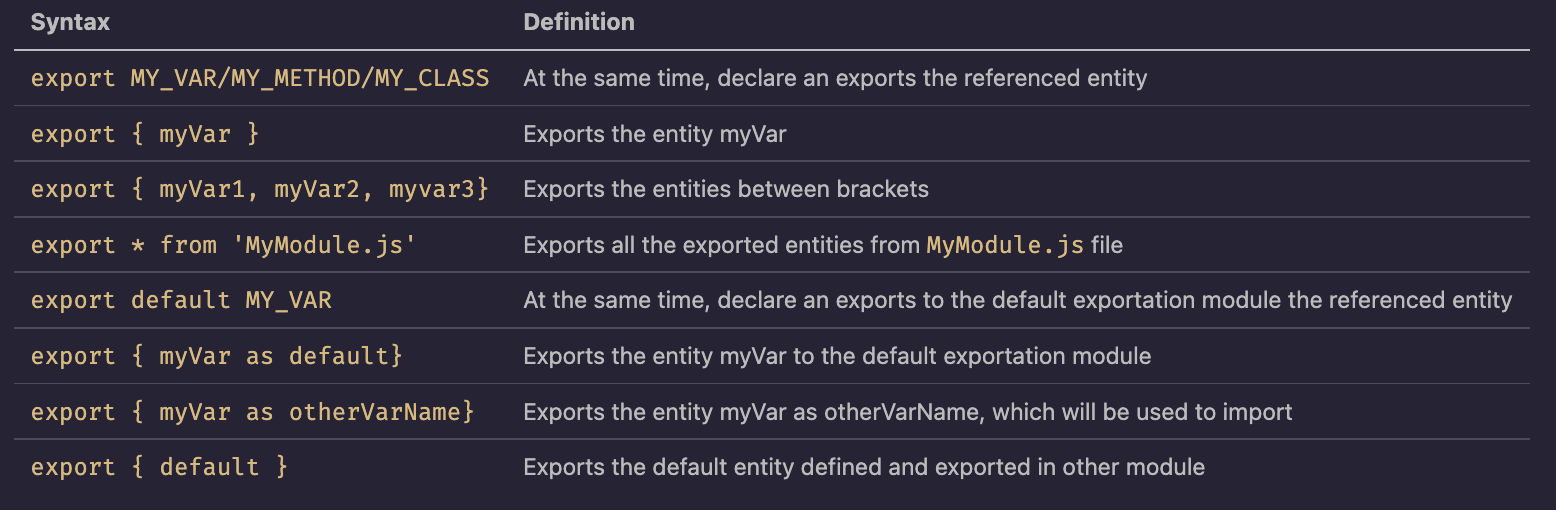

We have several ways of doing it, as we can see in the following table. It's important to note that all the export done in a file adds the export entity to the exportation module.

Important points to take into account:

- Only one default exportation is allowed per module

- When exporting an entity as default, is not allowed to use

var,letorconst - It's not possible to declare export within a function or loops

- It's not mandatory to export the entities when declaring them, we can export them at the end of the file for instance (as is usually done in NodeJS)

- Entities cannot be exported more than once

Importing

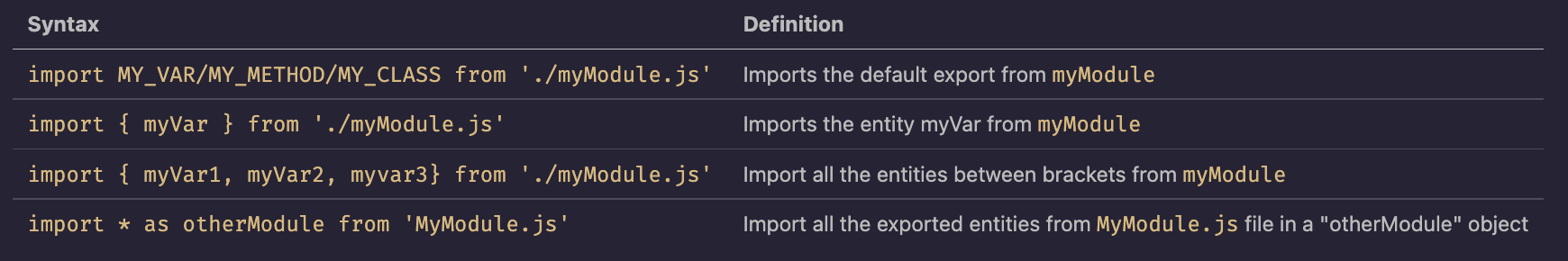

Importing is the way we access the data exposed in an exportation module. We have several ways of doing it depending on how we have exported the entities.

Examples

We have prepared some code that you can copy paste and execute directly. Just follow the instructions.

Non-web environment

- Name files as indicated

- Execute

node main.mjsornode main2.mjs

// module.mjs

const var1 = 1;

const var2 = 2;

const var3 = 3;

const var4 = 4;

const var5 = 5;

const var6 = 6;

export const var7 = 7;

export { var1 };

export { var2, var3 };

export default var4; // it is the same as export { var4 as default }

export { var5 as var6 }

export * from './otherModule.mjs';

//export { default } from './otherModule.mjs';

// otherModule.mjs

const otherModuleVar = 'other-Module-Var';

const myOtherModuleDefaultVar = 'my-other-module-default-var';

const myFunction = () => "hello"

export default myOtherModuleDefaultVar;

export { otherModuleVar, myFunction };

// bridgeModule.mjs

export * from './otherModule.mjs';

export { default } from './otherModule.mjs';

// main.mjs

import { var1, var2, var3, var6, var7 } from './module.mjs'

import defaultImportIsForVar4 from './module.mjs';

import { otherModuleVar, myFunction } from './module.mjs'

console.log(var1)

console.log(var2)

console.log(var3)

console.log(var6)

console.log(var7)

console.log(defaultImportIsForVar4)

console.log(otherModuleVar)

console.log(myFunction())

// main.mjs

import { var1, var2, var3, var6, var7 } from './module.mjs'

import defaultImportIsFormyOtherModuleDefaultVar from './module.mjs';

import { otherModuleVar, myFunction } from './module.mjs'

console.log(otherModuleVar);

console.log(defaultImportIsFormyOtherModuleDefaultVar);

console.log(myFunction());

Note that we are using mjs file extension. An MJS file is a source code file containing an ES Module for use with a Node.js application.

Web environment

- Name files as indicated

- Serve the files with

npx servefor instance

// main.js

import { var1, var2, var3, var6, var7 } from './module.js'

import defaultImportIsForVar4 from './module.js';

console.log(var1)

console.log(var2)

console.log(var3)

console.log(var6)

console.log(var7)

console.log(defaultImportIsForVar4)

// module.js

const var1 = 1;

const var2 = 2;

const var3 = 3;

const var4 = 4;

const var5 = 5;

const var6 = 6;

export const var7 = 7;

export { var1 };

export { var2, var3 };

export default var4; // it is the same as export { var4 as default }

export { var5 as var6 }

<html>

<head>

<script type="module" src="module.js"></script>

<script type="module" src="main.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

Modules

</body>

</html>

Bonus Track

Before we finish here, let's see other module related topics that are fascinating and closely related: Bare imports and Import maps.

Bare imports

Bare imports are the ones performed by indicating a string in from that does not begin with . or /, but directly by the name of a folder or package

import { moment } from "moment";

That means that probably the package will be searched on node_modules and some bundler is being used

Import maps

Import maps - a standard way to use bare imports. As described in the official Github repo, it gives control over what URLs get fetched by JavaScript import statements and import() expressions. This allows "bare import specifiers", such as import moment from "moment", to work.

The mechanism for doing this is via an import map which can be used to control the resolution of module specifiers generally. As an introductory example, consider the code

import moment from "moment";

import { partition } from "lodash";

<script type="importmap">

{

"imports": {

"moment": "/node_modules/moment/src/moment.js",

"lodash": "/node_modules/lodash-es/lodash.js"

}

}

</script>

Bibliography

- https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/learning-javascript-design/9781449334840/ch09s03.html

- https://github.com/umdjs/umd

- https://github.com/systemjs/systemjs

- https://riptutorial.com/javascript/example/16339/universal-module-definition--umd-

- https://bardev.com/2016/07/31/super-simple-systemjs-module-loader/

- https://github.com/WICG/import-maps

- https://www.sitepoint.com/using-es-modules/

Rafa Romero Dios

Software Engineer specialized in Front End. Back To The Future fan

See other articles by Rafa

WorksHub

Jobs

Locations

Articles

Ground Floor, Verse Building, 18 Brunswick Place, London, N1 6DZ

108 E 16th Street, New York, NY 10003

Subscribe to our newsletter

Join over 111,000 others and get access to exclusive content, job opportunities and more!